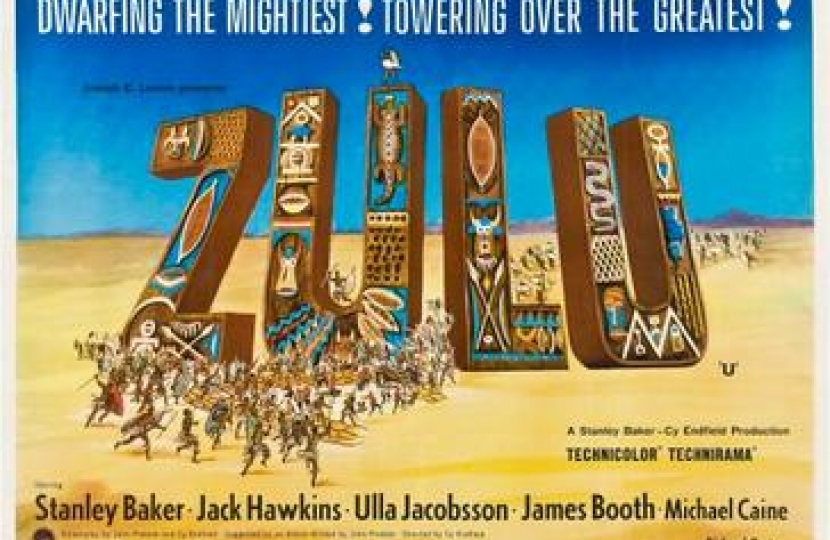

Those of you familiar with the great movie “Zulu” may recall the scene early on where a detachment of Boer volunteer cavalry led by Mr Stevenson arrive at Rorke’s Drift to tell Lieutenant Chard [played by Stanley Baker] that his regiment had been wiped out and that 4,000 Zulu are on their way to destroy his isolated outpost.

The exchange that follows sums up many of the misunderstandings that have bedevilled relationships between volunteers and professionals for generations – and which still have an impact on rural policing in the 21st Century.

Chard absorbs the disastrous news of the massacre, then asks Stevenson to lead his mounted men out to form a reconnaissance screen. But Stevenson refuses. He says “Look at my men. If they are going to die, they will die on their own farms. You are the professionals. You fight here if you want to.” Chard is aghast and angry, but despite his pleas the Boers gallop off.

Both men are quite correct from their own point of view. Chard makes what is undoubtedly the correct tactical military request in the circumstances. But Stevenson is also correct. His men volunteered as they thought that helping the British was the best way to protect their farms and families. Now that the British army had been destroyed, they needed to ride home to tell their wives and children to flee to safety before seeing what they can save in terms of livestock and stores before the Zulus arrive to destroy the farms.

The tragedy is that neither understands the motivations and needs of the other.

Some of the same problems persist when it comes to rural policing in the 21st century. There are plenty of residents in rural areas who want to help make their communities safer. By and large they understand that the sparse population and prevalence of unclassified roads make it difficult for the police to be everywhere at once. Many of them are willing to volunteer to help fill the gaps.

Much good work is done in rural areas by Neighbourhood Watch – the Rutland Neighbourhood Watch, for instance, have an excellent website HERE, and have developed their own app. While the Leicestershire Police have organised an excellent Rural Watch section – again with its own website HERE.

All good stuff. And yet…

Being a volunteer can be a deeply rewarding experience. I know, I’ve done it in many different guises. And having volunteers help you can be an amazing boost in even the most difficult and complex of tasks. But, as with Chard and Stevenson, things do not always run smoothly.

I must say that my experience of managing volunteers has largely come through politics. The Conservative Party in Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland delivers vast numbers of leaflets every year, and knocks on uncounted thousands of doors, and raises money for local and national campaigning. All of this takes huge effort by the thousands of volunteer members that the Party has across our city and two counties.

That effort has to be managed, directed and looked after. And managing volunteers is a specialised task. One that is far too often undervalued, and misunderstood. Our volunteers have their own reasons for stepping forward to donate their time and often their money or resources. Some volunteer because they like Boris, others because they support Brexit, some because they favour low taxes, others because they support the military and a few because they like a nice meal out with an interesting speaker. None of them expect or want to be paid. They come of their own volition.

Just as they have varied reasons for volunteering, they like to do different things. Some enjoy delivering leaflets as they walk around their neighbourhood, others like chatting to strangers on the doorstep and some actively enjoy colouring in maps for use at election time [it takes all sorts].

When managing volunteers, it is crucial to keep all this in mind. Volunteers turn up when they want to, and some are good at one thing, others at something else. Volunteers are not paid staff, and cannot be treated as if they were.

When looking to keep our rural areas safe from crime, the police need the help of volunteers. No matter how well disposed to our country dwellers and their problems our police commanders may be, there are simply not enough police to be in every village all the time. Eyes and ears on the ground are invaluable. And knowledge of tracks, paths and landscape is essential when seeking to crack down on illegal activities of all types. And anyone who has been on a horse knows that you can see far more from horseback than you can from a car.

Village communities can be tightly knit – even in these days when commuters have moved in and youngsters have moved out. A local will spot a vehicle from outside the area quickly, especially if it is behaving suspiciously. And the body language of a person striding along a footpath will often tell if they are there to admire the scenery, or case a farm for a robbery. Local people are out and about all the time. They see, they notice, they understand.

Rural volunteers need to be looked after. They need to be encouraged, given the correct equipment and directed into useful activities. But whoever is managing them also needs to understand that volunteers are not paid professionals. They are wonderful at what they do, but they should never be cajoled into tasks. They need to be understood. They need to be nurtured.

If a person volunteers because they love the village where they and their family have lived for generations, they will move heaven and earth by night or by day to help that village. But there is no point asking them to go to help out at a village 30 miles away. Like Stevenson and his horsemen asked to form a reconnaissance screen, they won’t go. Or if they do, they would resent it.

It is time to declare an interest. I am the Conservative Party candidate to be Police and Crime Commissioner for Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland. If elected, my patch will cover some of the finest rural areas in England.

I believe that working with volunteers offers a magnificent opportunity to the police. Neighbourhood Watch organisations are invaluable for collecting information on local crime problems – and also for passing out information on crime prevention. So are parish councils. And the same goes for volunteers outside of a formal network.

Our rural residents are among the most civic-minded and law abiding in the country. They want to help the police to protect their communities. They need to be given the tools they need to do the job. But the police must understand why volunteers come forward and how to manage them effectively.

If elected as Police and Crime Commissioner I intend to play a major role in helping our police force co-operate with volunteers in rural areas. We need to see a revolution in volunteering for the purposes of crime prevention and police co-operation.

It will take time, imagination and hard work. But I’m up for that. I look forward to working with our rural communities to make them safer.

This article first appeared in the Country Squire Magazine